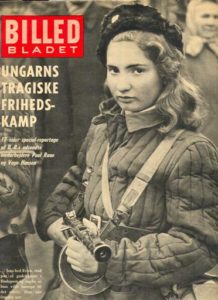

Sixty years ago the striking photograph of a teenage girl dressed in a cotton-wool jacket and clutching a Soviet PPSh-41 submachine gun became an iconic image of the Hungarian Revolution.

A Danish photojournalist, Vagn Hansen, had snapped the photo as Hungarian insurgents battled Soviet troops in the streets of Budapest in late October and early November of 1956. First published in the Danish magazine Billed Bladet, the photograph quickly was reproduced in newspapers and other publications around the world.

Hansen was one of a talented and brave group of foreign correspondents and journalists who covered the Hungarian uprising. Historian János Molnár has estimated that some 150 newsmen and women, most from the West, found their way to Budapest during the uprising.

The mass media coverage of the Hungarian Revolution offered an object lesson in the value of a free press. As the faltering Communist regime lost control of the borders, foreign correspondents were able to enter the country. Once there, the absence of government “minders” and censors allowed journalists to report what they saw, “without fear or favor of friend or foe.” The result: a balanced, independent, and accurate account of what was happening on the ground in Hungary.

This on-the-spot coverage had an impact. The stories, and pictures, of Hungarian insurgents resisting Soviet power helped illuminate the gap between Communist propaganda and the reality of life in the satellite nations of Eastern Europe. The brutal crackdown on the revolutionaries damaged the appeal of Marxist ideology in Western Europe and elsewhere, hurting the image of the Communist parties in France and Italy.

The reportage from Budapest also influenced U.S. foreign policy. Journalists found that many Hungarians believed, falsely, that NATO would intervene to defend the revolution based largely on Radio Free Europe broadcasts that had encouraged resistance to the regime. In response, President Dwight Eisenhower publicly claimed that the U.S. had never “urged or argued for any kind of armed revolt which could bring about disaster to our friends,” and privately curtailed rhetoric about rolling back Communism in the satellite nations.

Witnessing the revolution

While the uprising caught most Western news organizations (and intelligence agencies) by surprise, there were a few experienced newsmen in Budapest when students and workers began demonstrating against the repressive regime and the presence of Russian troops on October 23. Endre Marton of the Associated Press, John MacCormac of The New York Times (assisted by Aurél Varrannai), Sefton Delmer of the London Daily Express, and Leslie Bane of the North American News Alliance reported on the extraordinary events of the first hours of the revolt, the mass rally in Parliament Square, the battle over the Radio Budapest station, and the toppling of the giant statue of Stalin in Heroes Square.

Delmer filed an emotional first-person dispatch by telephone: “I have been the witness today of one of the great events of history. I have seen the people of Budapest catch the fire lit in Poznan and Warsaw and come out into the streets in open rebellion against their Soviet overlords. I have marched with them and almost wept for joy with them as the Soviet emblems in the Hungarian flags were torn out by the angry and exalted crowds. And the great point about the rebellion is that it looks like being successful.”

Soon more journalists arrived in the city, cramming into the Duna Hotel on the east bank of the Danube. Newspaper and wire service reporters and broadcasters came from the United States, England, France, Italy, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Polish and Yugoslav correspondents, who proved sympathetic to the insurgents, also filed reports.

Despite the danger, small groups of journalists ventured out to observe the street battles between the revolutionaries (many of them teenagers), and Soviet troops in places like the Corvin Passage and Széna Square. Photojournalists maneuvered to get close to the action. Michael Rougier of Life magazine shot a series of dramatic photos of the carnage that included images of burned-out tanks, bodies lying in the cobblestone streets, and makeshift graves of the fallen. Erich Lessing, an experienced Austrian photojournalist, documented the intensity of the fighting and the resulting devastation of the graceful boulevards and buildings of the city.

The journalists in Budapest didn’t shy away from reporting the often grisly scenes of the revolution. Marton and MacCormac were eyewitnesses to the massacre of civilians in front of the Parliament Building on October 24, when Russian tanks and secret police snipers killed hundreds. At the same time, there was no hesitation in reporting atrocities by the insurgents. Life magazine’s John Sadovy took disturbing photos of the summary execution of Hungarian secret police in Republic Square on October 30. One of the photographers on the scene, Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini of Paris Match, was hit by machine gun fire and later died from his wounds.

As the Red Army encircled Budapest in the first days of November, many foreign correspondents decided to leave while they still could. Some left with the convoys to Vienna organized by British and American diplomats. Nearly all of those who stayed after the Soviet onslaught of November 4, took shelter in Western embassies.

Two of the last Western journalists in Budapest were MacCormac and Russell Jones of United Press International. Jones, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the revolution, was expelled on December 5, and the János Kádár regime sent MacCormac packing on January 10, 1957.

After leaving Hungary, Jones challenged Soviet claims that the uprising was fomented on behalf of capitalists or large Hungarian landowners. “I saw with my own eyes who was fighting and heard with my ears why they fought,” he wrote, adding, “Wherever came the spark, it found its tinder among the common people. The areas of destruction, the buildings most desperately defended, and the dead themselves are the most eloquent proof of this.”

Despite the thousands of news stories filed about the Hungarian Revolution, the name of the girl with the submachine gun in Vagn Hansen’s iconic photo remained unknown until the 21st century. It was only then that researchers identified her as Erika Szeles, a young soldier and nurse. She was already dead by the time her photo appeared on the front cover of Billed Bladet, killed on November 8 trying to help a wounded friend during a firefight with Russian soldiers. Szeles was fifteen years old.

Jefferson Flanders is an independent journalist and author. His novel The Hill of Three Borders is set during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

This essay first appeared on RealClearHistory.

Copyright © 2016 by Jefferson Flanders