In The Tutor, an elegantly crafted novel that imagines William Shakespeare’s life during the early 1590s (during what scholars call his “lost years”), author Andrea Chapin accepts the notion that one of the world’s most famous writers was, indeed, the son of a glover from Stratford-upon-Avon, a provincial English town.

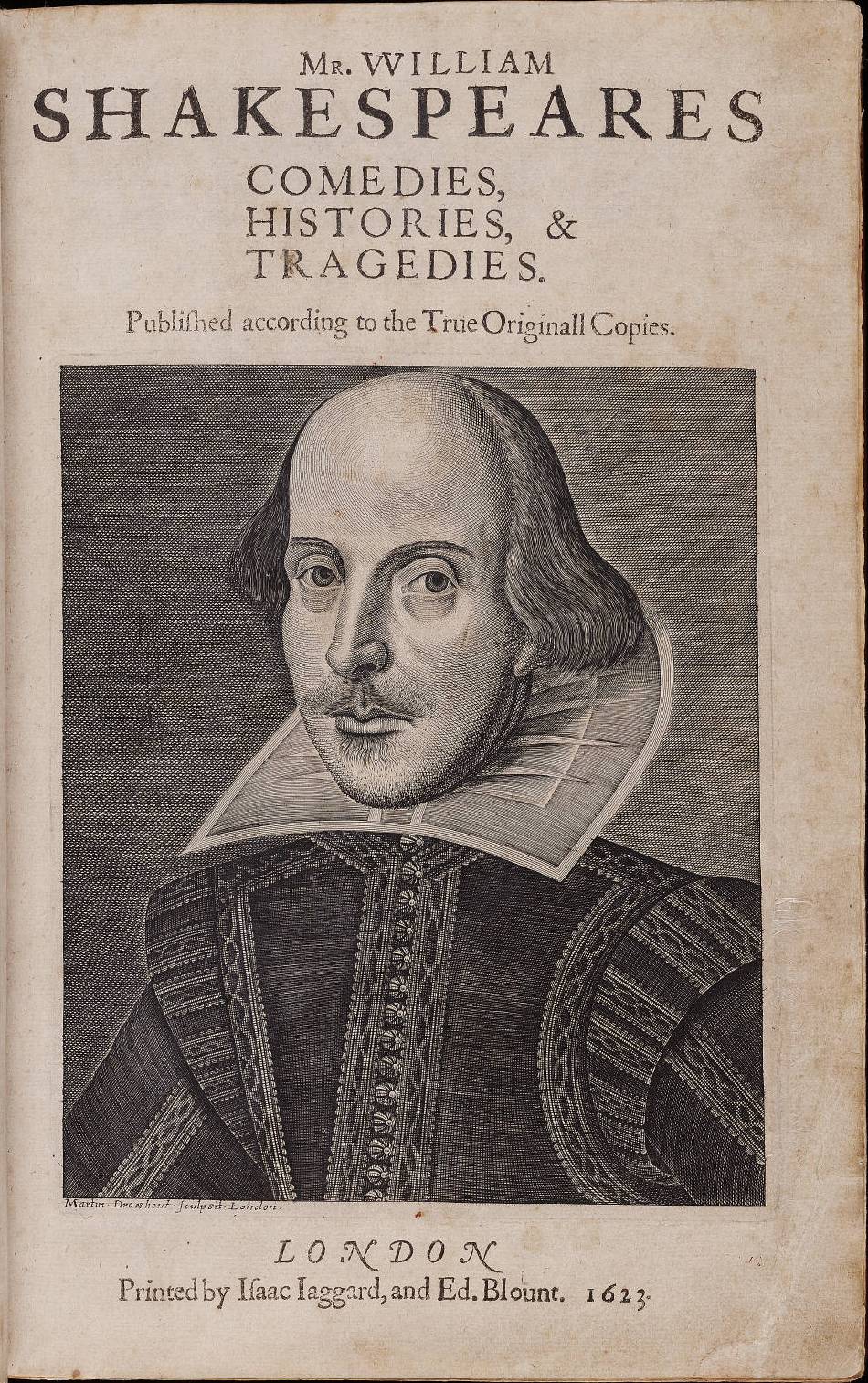

That’s a distinct improvement over the recent attempted rewriting of literary history in Anonymous, Roland Emmerich’s 2011 movie that depicts Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, as having secretly written Shakespeare’s plays. De Vere died in 1604, well before Shakespeare’s later plays were staged, but that doesn’t give the Oxfordians pause. They claim that de Vere must have left a cache of writings.

Another group of literary conspiracy buffs argue that Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor of England, is responsible for Shakespeare’s works. As with de Vere’s advocates, the Baconians claim that their man had the education, background, and biography to be a literary genius, and Shakespeare didn’t. They’re wrong. Columbia University’s James Shapiro does a masterful job of debunking Bacon-as-Shakespeare and the other candidates in his Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, noting that Shakespeare’s literary rivals and colleagues never called his authorship of what were very popular plays (and well-received poetry) into question.

In The Tutor, Chapin’s Shakespeare isn’t a fraud, but rather a man-on-the-make capitalizing on his gift of glibness. He’s a bisexual rake who manipulates men and women through his quick wit, personal magnetism, and brilliant acting. In the novel, Shakespeare is a schoolmaster, a tutor, to an aristocratic Catholic family in Lancashire. A young widow, Katherine de L’Isle, becomes Shakespeare’s muse and his quite critical line editor, as can be seen in this passage from the novel:

“…she dipped a quill in ink and started to write on Will’s pages, circling words, querying meaning and placement and feeling. Her lines stretched out at strange angles from his neat and careful handwriting, connecting his words to his. By the time she finished, the pages looked like maps, his words countries whose boundaries and allegiances had been called into question.”

Even while Chapin accepts the reality of the Stratford Shakespeare, she can’t resist introducing a classically-educated character to “improve” and inspire his writing. His torrent of sonnets and plays suggests, however, that Shakespeare didn’t need prodding to write, and apparently didn’t need much in the way of editing—one contemporary noted that his manuscripts had few corrections or revisions.

It’s hard for some university-educated types to accept that William Shakespeare, a commoner with (perhaps) a grammar school education, remains one of the world’s great authors. Yet I’ll argue, based on what I’ve seen in journalism and publishing, there’s little positive correlation between formal higher education and great writing ability. (In fact, ofttimes the more advanced degrees the writer holds, the more stilted the prose.) Look no further for proof than to those notable writers lacking academic credentials: Jane Austen, George Eliot, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, H.G. Wells, Jack London, George Orwell, Agatha Christie, Ray Bradbury, Maya Angelou, Gore Vidal, Doris Lessing, and Stieg Larsson.

There’s a reluctance to embrace this truth: a writer needs only imagination and a way with words to invent a believable world.

Writers need some education (apparently the grammar schools of Shakespeare’s time could be fairly rigorous), and I don’t mean to downplay the importance of research—I write historical fiction, after all. I suspect Shakespeare was a very curious man, and one who turned to people, and books, to learn what he needed to know for his plays.

I hold, however, that the creative Mind of the Maker (to borrow Dorothy Sayers’ wonderful term) counts for more than long hours in the archives. Even first-hand experience can be overrated, despite Ernest Hemingway’s admonition: “In order to write about life first you must live it.” A number of inventive fabulists (James Frey, Misha Defonseca, Margaret Seltzer, Greg Mortenson) have shown that a skilled writer can fool critics and readers into thinking that the imagined is real. (These authors have established a new genre: the false memoir.)

Other marvelous writers have demonstrated that, with enough craft and some diligent research, they can fashion a seamless fictional world with little or no first-hand experience. Experts on life in the Soviet Union raved about the accuracy of Martin Cruz Smith’s Gorky Park, and yet the novelist didn’t speak Russian and spent only two weeks in Moscow before writing his bestseller. Patrick O’Brian, author of the famous maritime series featuring Jack Aubrey, apparently couldn’t sail. Sid Smith’s Something Like a House, a novel about the Cultural Revolution, won Britain’s Whitbread First Novel Award and yet Smith couldn’t read or speak Chinese, and hadn’t worked in or visited China. Creativity, it seems, can trump biography. In fiction, what matters is that the reader believes.

At the same time, I do think accuracy in detail counts—especially in historical fiction. Getting things (geography, clothing, historical context) right helps the reader enter the different country of the past. I’m sensitive to anachronistic speech—I find it particularly jarring when a character uses slang or a phrase that doesn’t fit the story’s historical period.

In the end, what ends up on paper or in pixels must first emerge from the mind of the maker. Shakespeare noted the power of imagination for the poet:

The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

William Shakespeare, commoner, didn’t achieve title or rank, didn’t secure a position at court, and (from what little we know) didn’t travel extensively. But he had the poet’s eye, and that was more than enough.

©2015 by Jefferson Flanders