Another figure from post-war New York, from those golden years of the late 1940s and early 1950s, has slipped away: former middleweight prize fighter Roger Donoghue, Marlon Brando’s coach for his role as the washed-up boxer Terry Malloy in the remarkable film On the Waterfront, died this past week at the age of 75.

Budd Schulberg, who wrote the screenplay for the 1954 film credited Donoghue for inspiring the now-classic line from Malloy: “I could have been a contender.”

According to the New York Times, Donaghue saw athletic promise in Brando as he tutored the young actor in the sweet science:

To hear Mr. Donoghue tell it, Marlon Brando just might have been a contender himself. “I’ve got him shooting straight jabs, and he’s already learned to hook off the jab,” he said after the first lesson, according to Mr. Schulberg in a widely syndicated article. “I can make a hell of a middleweight out of this kid.”

“Roger,” Mr. Schulberg replied, “just let us get through this movie with him in it. Then you can have him back and take it from there.”

(Had Brando tried his hand at boxing, however, it’s unlikely he would have had the discipline to stay in the middleweight class—at least not judging from his massive weight swings later in his career.)

Donoghue knew his boxing. Before he was hired to train Brando, he had a brief career as a middleweight fighter. His one appearance at Madison Square Garden, in August 1951, ended in tragedy: Donoghue knocked out 20-year-old George Flores (a boxer he had defeated, also by KO, two weeks earlier) in the eighth round—and Flores died some five days later.

Donoghue donated his purse to the Flores family and stopped boxing shortly thereafter. He was promoting Rheingold Beer when he was recruited to coach Brando.

The best of the 20th century?

Director Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront is a marvelous film and, it can be argued, the best American motion picture of the 20th century. The film was based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning series by New York Sun investigative reporter Malcolm Johnson which exposed the control of organized crime over New York’s waterfront. It is a testament to New York’s post-war Golden Age in journalism, literature, music, and theater, an amazing period of creativity and artistic innovation in the decade after the end of World War II.

On the Waterfront tells the story of an average man, Terry Malloy, an ex-boxer and longshoreman who slowly realizes that he must stand up to the corrupt and brutal union bosses who rule the docks through fear, intimidation and violence. Kazan captures Malloy’s struggle of conscience and follows his difficult path to redemption; Malloy knows that telling the truth means not only being branded a “snitch,” but also putting his own life and future at risk. While the movie closes with Malloy publicly defying the mobsters, despite a savage beating, and gaining the support of his fellow dockworkers, there is nothing triumphal about the ending, no sense that Malloy has won a permanent victory.

On the Waterfront‘s themes—of loyalty and betrayal, of courage and of compromise, of the morally ambiguous role of the informer—carried deep personal resonance for its director. In 1952 Kazan had renounced his Communist Party past and “named names,” identifying eight of his colleagues from the Group Theater in the 1930s as Communists, in testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Kazan’s decision to testify, rather than plead the Fifth Amendment, outraged many in Hollywood, including playwright Arthur Miller, once a close friend.

It’s been argued that Kazan (and Schulberg, who was also a friendly witness before HUAC) sought to justify their actions in On the Waterfront, to show that an informer could be acting out of integrity, and that it took courage to testify against former friends, to “name names.” That may be so, but what ends up on the screen isn’t much of an advertisement for whistle-blowing, but rather a sobering consideration of the harsh consquences of informing.

Moreover, On the Waterfront deserves to be considered—or reconsidered—on its merits, not as propaganda or polemics, but as an artistic work.

Reconsidering the movie

One reason On the Waterfront remains vital today is because it is film-making at its best: the movie offers a blend of brilliant acting, sensitive cinematography and a complementary score coupled with a restrained direction that allows individual performances to emerge and dazzle.

The collection of talent employed in this low-budget black-and-white film, shot on location in Hoboken over some 36 days, was stunning. Many of the actors were alumni of the legendary New York Actors Studio. Kazan assembled a cast that included Marlon Brando, Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger, Eva Marie Saint, Pat Henning and James Westerfield (and Fred Gwynne and Martin Balsam in small roles). Three ex-heavyweight boxers, Abe Simon, Tony Galento, and Tami Mauriello played union thugs, and many of the extras were real life dockworkers.

The cinematographer, Boris Kaufman, worked wonders; he used the shabby Hoboken cityscape and the constrast between the cramped apartments and open roof-top skylines to give a sense of place and time. Kaufman proved to be a master at employing the winter afternoon light (helped by the judicious use of trash fires) to soften the look of the film. And composer Leonard Bernstein’s haunting themes, recurring throughout the film, provided additional emotional depth to the story.

Kazan was lucky just to get the movie made—the screenplay was initially turned down by the major studios (Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox dismissed the project with this memorable comment: “All you’ve got is a lot of sweaty longshoremen. Exactly what the American public doesn’t want to see.”) and the financing came from producer Sam Spiegel, a relative Hollywood outsider, who eventually persuaded Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures to take on the project.

Assembling the cast wasn’t easy, either. Brando supposedly balked at working with Kazan because of his HUAC testimony. Frank Sinatra was recruited for the part of Terry Malloy before (with Spiegel’s prodding) Brando relented and joined the project. Lee J. Cobb, who played the thuggish union boss Johnny Friendly, had no such problems—he had also testified before HUAC.

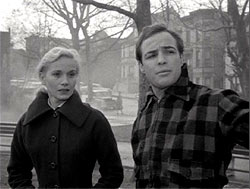

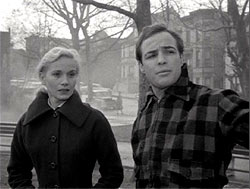

Eva Marie Saint was selected after Grace Kelly passed on the part of Edie Doyle in order to appear in the The Country Girl (for which Kelly won an Oscar). Kazan saw in Eva Marie Saint what audiences did: a beautiful young woman radiating innocence and an appealing gentleness, perfect for the part of the idealistic, yet passionate, Edie.

Rod Steiger was cast as Charlie “the Gent” Malloy, Terry’s older brother, because a better-known actor, Lawrence Tierney, had demanded too much money. Steiger later claimed he would not have participated if he had known about Kazan’s testimony (a claim that is hard to believe), and he proved to be particularly nasty over the years about what he saw as Kazan’s connection (however strained) to the Hollywood blacklist.

Kazan clearly got lucky, I think, with the cast, especially with his two leads. It’s hard to envision On the Waterfront with Frank Sinatra as Terry Malloy and Grace Kelly as Edie Doyle: Sinatra is too sharp, too self-aware for the role, and Kelly seems too elegantly upper-class to be believable as the sheltered Edie. Brando and Eva Marie Saint seem to have been born to play their parts.

Quiet scenes

What makes On the Waterfront such a marvel, I would argue, is not only the acting, but the restraint in Kazan’s direction.

Take the scene where Terry Malloy walks Edie Doyle home through the park. When she drops one of her gloves, Malloy picks it up, and (an action Brando improvised in rehearsal) plays with it, eventually slipping his hand into it. Kazan kept the improvisation in the scene—and it works on several levels: it foreshadows Terry’s sexual interest in Edie, and also, some have argued, his “trying on” Edie’s “white glove” morality.

Kazan also left untouched a risky scene written by Schulberg. When Terry confesses his role in the death of Edie’s brother, he unburdens himself to her by the waterfront. As Terry begins to explain to Edie, we can not hear his words—they are drowned out by the blast of a whistle from a departing ship—and the camera shows us only Edie’s horrified reaction. Instead of being distracted by Terry’s dialog we focus solely on the crushing impact of the news on the sensitive Edie.

These two quiet scenes are part of what gives On the Waterfront some of its lasting power. They connect us to the story in personal, not political, ways.

That is not to say that there isn’t some message-heavy clumsiness in the film. Kazan and Schulberg lay on the Christian symbolism of sacrifice a bit too thick at the end of the film—but they can be forgiven that lapse, for the movie as a whole has a unity rarely found in American film.

Taking stock

On the Waterfront received critical acclaim in its own time—eight Academy Awards including best picture, best actor, best supporting actress, best art directon, best cinematography, directing, film editing, and screenplay for 1954. There were also nominations for Bernstein’s score and for best supporting actor for Cobb, Malden, and Steiger.

Beyond its sheer technical excellence, I think the reason the movie remains compelling more than half-a-century after its initial release is that it deals with questions that time has not (can not) neatly resolve. When is informing the morally correct choice? What are the costs of compromising in the face of wrongdoing? What loyalties must we honor? What sacrifices must we make? (Sometimes overlooked is the moral decision Charlie Malloy makes at the end of On the Waterfront: he can not betray his brother to Johnny Friendly, and that loyalty costs him his life).

To inform, to become a whistleblower, is to challenge often unspoken assumptions. Our uneasiness with the idea is illustrated by the harsh words used to describe an informer: tattle-tell, rat, fink, snitch, pigeon, cheese-eater, stool pigeon, stoolie. Much of the world looks askance at those who “drop a dime” or “sell out” their buddies, their comrades. In On the Waterfront, the dockworkers credo is “D and D”—deaf and dumb.

What culture, corporate or political, doesn’t prize loyalty? The roots of loyalty are tribal; from a time when unquestioning obedience, unity, and “closing the ranks” had life-or-death ramifications. The informer rejects those bonds of comradeship and cohesiveness.

Ideally, the whistleblower answers to individual conscience and the more abstract call of justice for the larger community—which often means justice for strangers—although in practice he or she may also be motivated by baser motives of ambition or revenge, or a desire to avoid prosecution.

Some of our ambivalence may be traced to our suspicions about the mixed motives of informers, especially those who seek anonymity. To recite the names of famous (or infamous) American political whistleblowers—W. Mark Felt, John Dean, Daniel Ellsberg, Whittaker Chambers, Scooter Libby—is to illuminate the problem. They may not be completely free of culpability themselves. They may be plagued by a guilty conscience. They may be out for revenge or vindication.

What gives On the Waterfront its timelessness is that Kazan understood this ambivalence. How could he not? The movie reflects this moral ambiguity—for those who testify against former friends and colleagues, and for those who will judge them—through the awakening of Terry Malloy, a reluctant hero, one with no appetite for what he is driven to do. There is no “cheap grace” (to use Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s term) for those who inform, whatever the reason and no matter how virtuous their cause may seem, a truth that Kazan knew only too well.

Copyright © 2006 Jefferson Flanders

All rights reserved

Jefferson Flanders is author of the Cold War thriller Herald Square.