OSLO — I’ve spent the past two weeks in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway visiting museums and researching Norse history with an eye to, perhaps, one day writing a novel about the Vikings and their 11th century encounter with the First Peoples.

While I’ve been traveling, elite literary circles have been roiled over the question of “cultural misappropriation,” of whether “white” writers should refrain from writing about the experiences of minorities (the Other). As a novelist whose work has touched upon other cultures, I’ve watched the debate with interest, and with some dismay.

It began when American novelist Lionel Shriver argued at the Brisbane Writers Festival that “fiction writers should be allowed to write fiction — thus should not let concerns about ‘cultural appropriation’ constrain our creation of characters from different backgrounds than our own.” Her challenge to the notion of “cultural purity” was not well received by the literary left, which has embraced identity politics with a vengeance. The New Republic ran a response by Lovia Gyarke entitled “Lionel Shriver Shouldn’t Write About Minorities.”

I suppose under the new rules of cultural purity, my Viking novel would be acceptable. You see, one side of my family is Swedish (my maternal grandmother, Mormor, made meatballs as succulent as any in Stockholm), and the other side claims Native American ancestry from the colonial period. Of course, it’s absurd to think that matters. My DNA should have nothing to do with my writing a Viking novel.*

There simply shouldn’t be any barriers based on identity. The gay Jamaican novelist Marlon James, winner of the Man Booker Prize, has made this point, noting that while he is known for his Caribbean fiction: “I’ve been threatening to write a Viking novel for almost 10 years now.”

In my view, the only question a novelist needs to answer is: Am I drawn to tell this story? I know I won’t make the necessary investment in time and energy unless I can answer with a strong “yes.”

I’ve fashioned characters from different cultures, different walks-of-life, different sexualities, different races. That’s what writers do. That isn’t to say that culture doesn’t matter. It does. But love, jealousy, resentment, lust, hate, joy, and all the other emotions human feel are not restricted by age, class, or time period. (Read Li Bo’s Tang Dynasty poems of longing to be reunited with his wife, Zong, or the tortured and erotic love poems of Catullus. Universal. Timeless.)

Some writers will butcher cultures that aren’t their own. They’ll condescend or distort or stereotype. In short, they’ll fail. But so what? That’s a small price to pay for artistic freedom. There will be misses, but also hits.

I’d like to believe that this ugly intrusion of identity politics into the imaginative world will pass. There’s a not-so-faint whiff of the totalitarian in the campaign to narrow what’s “acceptable.” Even those sympathetic to the cultural purity argument who think fiction should be politicized, like Jess Row, admit that there’s a chilling effect for “white” writers (“What made you feel you had the right to write that book?”)

The best course for a writer is to carry on and ignore the static. I’m not going to let calls for literary cultural purity change what I choose to write about; I’ll let readers decide if I’ve hit or missed the mark. And if Marlon James ever does publish his Viking novel, I’ll be sure to read it.

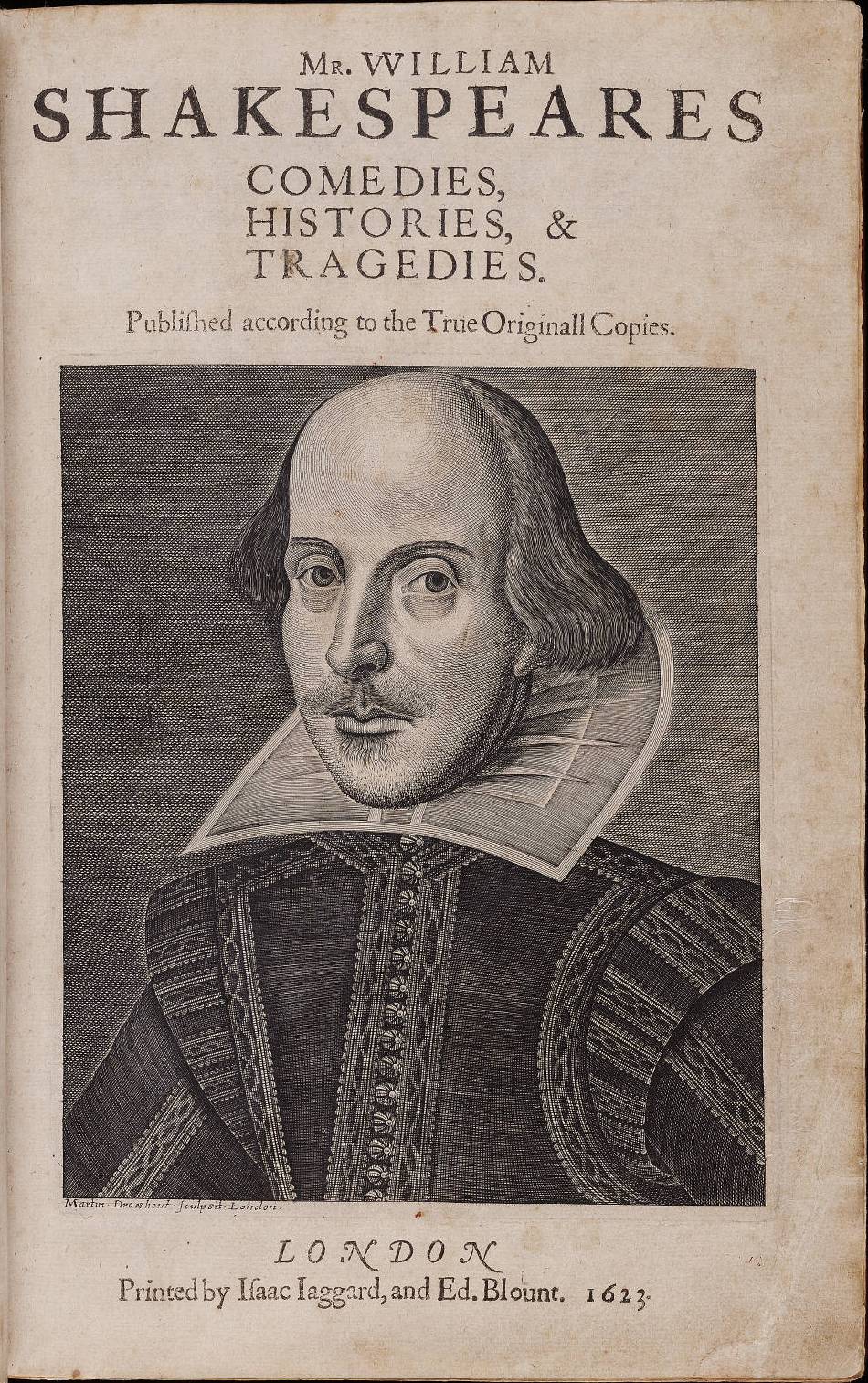

* Shakespeare somehow managed to fashion Othello and Shylock without being African or Jewish. I find Kazuo Ishiguro’s English butler of the 1930s, Stevens, completely believable. (And Yo-Yo Ma plays Baroque music brilliantly, and Misty Copeland does more than justice to Balanchine’s classical ballet steps.)

Copyright © 2016 by Jefferson Flanders