What are the best spy novels of 2018? Here’s a list of my top picks (as they are published throughout the year). Please note that I’m partial to historical fiction about espionage that has a literary flair; the novels I’ve selected reflect that bias.

(I’ve not included my own 2018 spy thriller, An Interlude in Berlin, in this list but if you’re interested, Kirkus Reviews called it “an engrossing tale of intrigue and duplicity,” and you can find it here.)

Transcription by Kate Atkinson

In hindsight, the victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany seems inevitable. At the time, however, particularly in the early stages of World War II before the U.S. entered the conflict, it wasn’t clear that Great Britain would be able to resist the German onslaught. Hitler’s blitzkrieg had brought the Continent under Nazi control. And there were members of the British elite who wanted to sue for peace, and some who even rooted for a German victory.

Kate Atkinson’s novel Transcription explores the efforts of MI5 to monitor the potential Fifth Column of British Fascists during the initial stages of the war. Her protagonist, Juliet Armstrong, is an inexperienced 18-year old who is recruited by British Intelligence and employed as a typist creating transcripts of bugged conversations between would-be German agents. She quickly graduates to infiltrating a cell of upper-class Nazi sympathizers. Juliet, who has some secrets of her own, finds the covert work alternatively comic and terrifying.

Atkinson is a talented and fluid writer and Transcription, while slow-moving at times, is cleverly constructed and laced with a dry humor. The novel shifts back and forth in time from 1950 (when Juliet has become a radio producer at the BBC) to the early war years, and Atkinson has a flair for capturing the details of the period. The conclusion of Transcription is much less convincing than it could be, however, as the necessary backstory that would have made the reader buy into the twist ending isn’t fully developed.

The Other Woman by Daniel Silva

Daniel Silva’s series of Gabriel Allon novels have, for the most part, centered on the struggle between Israel and its adversaries, whether Islamist regimes or jihadist terrorists. His latest, The Other Woman, focuses instead on the threat to the West presented by the authoritarian regime in Moscow and its leader, a former KGB officer.

Fans of Allon—the art restorer, assassin, and head of Israel’s secret intelligence service—will find much in Silva’s latest thriller that is familiar. Once again, Allon and his team of loyal agents roam across Europe, from Vienna to London to Bern to Seville to Moscow. This time they are in pursuit of a sleeper mole deep in the heart of MI6, a task Allon has taken on at the request of his British counterpart. As their hunt continues, the clues point to the mole’s connection with the infamous double agent Kim Philby who defected to Moscow in 1963 (and died there in 1988 at the age of 76 just before the collapse of the Soviet Empire).

The novel’s central premise, that the KGB could have inserted a mole into MI6 during the Cold War, isn’t wholly implausible. In 2010, ten Russian sleeper agents in the U.S were arrested. They were living under assumed identities, tasked with political and industrial espionage, and had been in the country for more than a decade in deep cover. (This spy ring was the inspiration for the FX series The Americans.) Were there other penetration agents in the West, whose control was passed from the KGB to the SVR after the end of the Cold War? The Other Woman suggests that there were; Silva fashions an intriguing take on how that might have happened.

Paris in the Dark by Robert Olen Butler

The talented and prolific author Robert Olen Butler, who won a Pulitzer Prize in fiction for his lyrical Vietnam-themed short stories (A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain), has recently turned to writing historical spy thrillers. The books feature Christopher Marlowe Cobb, an American journalist/spy with a taste for action. Butler’s latest, and fourth in the series, Paris in the Dark, brings “Kit” Cobb to the French capital in autumn 1915, before the U.S. joined the Allies in their bloody struggle with the Kaiser’s Germany.

While Cobb researches a story about American volunteer ambulance drivers, Paris is rocked by a string of bombings. He is tasked with finding and neutralizing the bombers, while maintaining his cover as a newspaper reporter. As Kit Cobb searches for German agents, the clues lead him in a different direction. Butler knows how to tell a compelling story, and how to develop characters the reader cares about, the most intriguing of which is the lovely young American nurse, Louise Pickering (Cobb’s love interest). Paris in the Dark rewards us with a suspenseful and satisfying ending, one that resonates with more modern concerns about terrorism.

Butler’s attention to period detail is impressive with his evocative descriptions of 1915 Paris. The novel also reminds us that Bolsheviks weren’t the only revolutionary socialists active in the early twentieth century—anarchists were also seeking the violent overthrow of the existing order. (One of the earliest spy novels, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent featured an anarchist.) Violence against the ruling class was common. In the decades before the start of the First World War, anarchists assassinated three kings (Italy, Spain, and Greece), the prime minister of Spain, the presidents of France and the United States, and a Tsar (Alexander II of Russia).

Safe Houses by Dan Fesperman

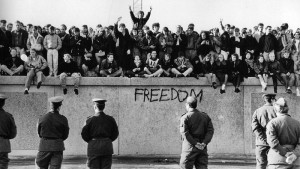

Dan Fesperman tells two stories in his latest thriller, Safe Houses. One begins in 1979 when a young CIA officer, Helen Abell, overhears conversations in a West Berlin safe house that she isn’t meant to—with unintended and dangerous consequences. The other story commences in 2014 after a brutal double murder in a quiet Maryland Eastern Shore town. A young woman teams up with a former Congressional investigator to try to understand why her parents died. Exploring the hidden connections between these stories lies at the heart of Fesperman’s carefully-constructed tale, and he manages to skillfully manage the back-and-forth in time and place.

While it offers suspenseful plot twists, Safe Houses isn’t a traditional Cold War spy novel—it pays scant attention to clashes between the KGB and Western intelligence agencies. Instead, it delves into the internal politics of the CIA, and the way its Old Boy network treated female employees three decades ago. Fesperman takes a decidedly feminist slant on that history (no doubt influenced by the #MeToo movement that began in 2017), and the novel reminds us of the struggles women faced (and face) in male-dominated organizations. Safe Houses focuses on the female pioneers of the CIA, during a time when they were marginalized and constrained to clerical roles. Much has changed: today, the director of the Agency is a woman.

The Hellfire Club by Jake Tapper

Did you enjoy Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code? Or the movie National Treasure? How about Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter? If you like mashups of historical fact, popular culture, and over-the-top conspiracy theories, then you’ll relish Jake Tapper’s political thriller The Hellfire Club. Tapper, CNN’s chief Washington correspondent, has set his novel in Washington, D.C. in the spring of 1954, and it includes all the elements of a breathless (but slightly campy) thriller, offering cameos from political figures of the period including President Dwight Eisenhower, Roy Cohn, Allen Dulles, and Senators Joseph McCarthy, Estes Kefauver, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and Margaret Chase Smith.

The novel’s protagonist, New York Republican congressman Charlie Marder, had just arrived in Washington to assume his seat. After too many cocktails at a party with the DC elite, Charlie finds himself entangled in a Chappaquiddick-like incident that makes him vulnerable to blackmail. Despite being a decorated World War II veteran, Charlie is no Profile in Courage when push comes to shove, folding when pressured by a sinister cabal to vote against his conscience and to aid the McCarthy witchhunt. His better half, Margaret, a zoologist, proves to be a sight better on ethical questions, and she helps Charlie maneuver his way through a suddenly-treacherous landscape where friends may be adversaries (and vice versa). Tapper rachets up the suspense; there are mysterious clues, hidden allies, secret societies, and a car chase or two.

Some of the blurbs for The Hellfire Cub suggest that the book is “vividly relevant” in the Age of Trump. That is, to put it mildly, absurd, unless you believe that Deep State operatives in the Swamp secretly decide the fate of the country, aided by amoral Republicats. Then again, as Apollo astronaut Neil Armstrong once noted about claims that the moon landing was faked: “People love conspiracy theories.”

The Dark Clouds Shining by David Downing

One of the harder things for any novelist is to seamlessly introduce the necessary context—the key backstories—in a sequel. What storylines from prior books need to be continued or expanded? How should recurring characters be handled? How to accomplish all of this smoothly? David Downing begins his fourth and final Jack McColl thriller, The Dark Clouds Shining, with a clever opening that addresses these challenges: it’s March 1921, and McColl, an ex-British spy, is in the dock in a British court for assaulting a police officer—and his trial helps illuminate McColl’s past, including his disillusionment with Great Britain’s imperialistic foreign policy. After his conviction, McColl is approached by the Secret Service and offered a chance to wipe his record clean if he’ll agree to a clandestine mission in post-revolutionary Russia.

McColl has been tasked with surfacing, and possibly neutralizing, a convoluted assassination plot hatched in Moscow that is meant to provoke conflict in British-ruled India. (Yes, it is convoluted, but engaging). McColl is persona non grata in Russia; he must worry not only about the Soviet secret police but also the threat from the assassins, led by McColl’s nemesis from the past, Aidan Brady, a radical with a violent streak.

The Dark Clouds Shining portrays a Russia where Lenin and the Bolsheviks, having won their country’s civil war, are consolidating power, suppressing their ideological rivals by force. The purges and show trials are yet to come, but it’s clear that state terror is in the cards.

Once in Moscow, McColl is reunited with his lover, the American journalist Caitlin Hanley. She is the most intriguing of the characters in the novel. A feminist who believes in the revolution’s promise of equality for women, Hanley accepts revolutionary excesses as a means to her desired ends—the Faustian bargain that many radicals make in pursuit of their goals.

David Downing is known for his attention to historical detail, and his sympathetic vision—his characters are conflicted and flawed, just like their real-world counterparts. It’s his understanding of human nature, and his compassion, that elevates Downing’s novels. We can only hope that as this series concludes that additional books are in the offing.

Greeks Bearing Gifts by Philip Kerr

The sad news about Scottish novelist Philip Kerr’s death came in March; Kerr, 62 years old, had lost his battle with cancer.

Just weeks earlier his 13th Bernie Gunther novel, Greeks Bearing Gifts, had been published in the United States. In the past, readers and critics alike had avidly followed the adventures of Gunther, the hard-boiled former Berlin detective, as Kerr told the horrific story of the Third Reich and the shadowy struggles of the early Cold War through the eyes of his world-weary protagonist. Gunther is no hero; he’s a man who compromises and looks the other way in order to survive. Boxed in by the Nazi criminals who have become his superiors, he tries to keep his hands as clean as he can, knowing that at some level he is complicit. Gunther’s defense mechanism against the cruelty of the world is a cynical and sardonic humor.

Greeks Bearing Gifts, set in 1957, finds Gunther living in Munich under an assumed name (Christoph Ganz), hiding from assorted spy agencies and the authorities, for, as he says, “I had more dirty water in my bucket than most…” When Gunther/Ganz is offered a job as an insurance claims adjuster for Munich RE, he hopes to start a new and quieter life. But when he is sent to Greece to investigate a claim by a German owner of a yacht that has burned and sunk in the Aegean sea under suspicious circumstances, the case turns quite dangerous.

Bernie Gunther novels are filled with memorable characters, and Greeks Bearing Gifts is no exception. There’s an oily Munich lawyer with a shared past with Bernie, a timid Greek insurance agent named Achilles, an honest Athenian cop who makes use of Gunther’s talents in investigating a murder, an alluring young Communist attorney, and colorful minor players who help keep the pages turning. It’s a dark story that involves the wartime murders of Jews in Salonika and the confiscation of their property and money, and a sadistic SS officer who surfaces with an unresolved mission.

As is his wont, Kerr mixes in pointed historical commentary. Greeks Bearing Gifts explores the debate over the question of German reparations to Greece. Kerr makes it clear his distaste for Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of West Germany, who didn’t exclude all Nazis from German society or its government, and who didn’t pursue payments to Greece for the devastation caused by the Nazi occupation. (Der Alte, who was an anti-Nazi leader during the 1930s, did push for reparations for Israel, and accepted Germany’s responsibility for the “unspeakable crimes” of the Holocaust).

But Adenauer allowed the reintegration of morally compromised German businessmen and lawyers. He reasoned that a strong West Germany (the “economic miracle”) was necessary as a bulwark against Soviet aggression, believing that the Russians represented an existential threat to liberal democracy. While it helped advance European integration, the Faustian bargain that Adenauer struck was to haunt Germany and provoke unrest in the mid-1960s. As Ian Walker has noted: “The Germany he created just didn’t look back. There was an unhealthy silence at the heart of Germany’s sense of itself.” For too many, there’s been a willingness to ignore the crimes of the Nazi era, a willed amnesia that continues even today over the issue of prosecuting war crimes.

Kerr leaves Bernie Gunther’s future unresolved at the end of Greeks Bearing Gifts, hinting at a redemptive return to Germany; his publisher announced that before his death Kerr had finished a final book, Metropolis, which would appear in 2019.

Babylon Berlin by Volker Kutscher

In January, Picador published a paperback edition of the first novel in Volker Kutscher’s noirish series about a detective in Weimar Germany, a publication timed to capitalize on the interest generated by Netflix’s airing of the “Babylon Berlin” miniseries.

The novel, titled Babylon Berlin and translated by Niall Sellar, had been published in Germany in 2008 as Der nasse Fisch (in English, The Wet Fish). It features Gereon Rath, an ambitious police inspector who has moved from Cologne to join Berlin’s vice squad and is looking to make a name for himself. As Rath tries to solve the mystery of an unidentified murder victim fished out of the city’s Landwehr canal, he discovers a cell of Russian Trotskyists is scheming to exchange smuggled gold for weapons in the hopes of deposing Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Rath’s investigation entangles him in a dangerous and complex world of political intrigue that hits closer to home than he, at first, realizes.

Babylon Berlin explores the dark side of life in Germany’s capital in 1929: Communists and Nazis plotting to bring down the government of Social Democrats; an underworld of nightclubs, cabarets, and brothels; and neighborhoods mired in crime and poverty.

Those who have watched the Netflix series will find significant differences between the novel and the televised version. The main characters are shared: Inspector Rath; Charlotte Ritter, a would-be detective working as a typist in Homicide who attracts Rath’s romantic interest; and the cynical Vice squad head, Bruno Wolter, who has links to reactionary elements in the military. But the screenwriters (Tom Tykwer, Hendrik Handloegten, and Achim von Borries) created additional characters, added backstories, and altered aspects of the plot.

The novel is a well-crafted police procedural, with less of the political and social background that makes the miniseries a compelling watch. For those who enjoy historical thrillers, both the novel and the series are well worth the time.

Munich by Robert Harris

History’s verdict on Neville Chamberlain, the prime minister of Great Britain from May 1937 to May 1940, has been harsh—he’s seen as Adolf Hitler’s prime enabler, a weak old man whose policy of appeasement emboldened the Nazi dictator and inevitably led to war.

The accomplished and prolific novelist Robert Harris has constructed his latest historical thriller, Munich, around the infamous 1938 meeting in Bavaria’s capital city where Chamberlain, along with French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, met with Hitler and the Italian Duce Benito Mussolini and agreed to German annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland.

Munich takes place over the last four days of September, 1938, focusing on the diplomatic maneuverings of the Four Powers to address Hitler’s ultimatum about Czechoslovakia. Diplomacy is conducted in a blizzard of paperwork—speeches, memos, telegrams, dispatches, war plans. The novel follows two junior, multilingual diplomats, an Englishman, Hugh Legat, and his German friend, Paul von Hartmann, who attend the Munich conference and are called upon to translate and interpret for their superiors. (The two became close while students at Oxford in the 1920s.)

Hartmann has joined the Oster Conspiracy, a plot hatched by Hans Oster, deputy head of the Abwehr (German military intelligence) to depose Hitler should he order the invasion of Czechoslovakia and risk a wider and unpredictable conflict. Hartmann enlists a reluctant Legat to help, hoping that exposing Hitler’s true expansionist intentions (the dream of an Aryan Lebensraum reflected in secret war plans) will convince the British to scuttle any agreement. It’s a dangerous mission, with German security forces alert for subversion. To Harris’ credit, Munich is a novel filled with suspense—no easy task when the reader knows the eventual historical outcome.

The novel is deeply researched, blending fact and fiction effortlessly, and rich in period detail (a characteristic of Harris’ books). Munich captures the strong anti-war sentiment in Great Britain, France and Germany. There was a reason that cheering crowds greeted Chamberlain upon his arrival Munich—the memories of the First World War and its ten million dead were still raw. (The mindless slaughter of that conflict is depicted in all its horror in John Keegan’s magisterial The First World War; in Chapter 9, “The Breaking of Armies,” Keegan describes the gory reality for the British, Australian, and Canadian troops in the nightmarish Third Battle of Ypres.) The popular desire for peace was genuine.

Munich raises a series of provocative historical questions. Did Chamberlain concede the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia not only in hopes of “peace in our time,” but also because, as Harris suggests, he was conscious of the relative inferiority of the British army and air force compared to the German war machine? Did he seek to buy time for Great Britain to rearm? In the novel, Chamberlain laments: “The main lesson I have learned in my dealings with Hitler is that one simply can’t play poker with a gangster if one has no cards in one’s hands.” (Certainly Daladier felt he had negotiated from a position of weakness; he later commented: “If I had three or four thousand aircraft, Munich would never have happened.”)

Or did Chamberlain and Daladier squander a chance to confront Hitler? What if France and Britain had stood fast at Munich and risked war with the Axis Powers? As Winston Churchill pointed out in his brilliant speech to the House of Commons on October 5th, 1938, that faced with Allied resolution, Hitler would have paid a high price for the Sudetenland; the Wehrmacht would have confronted a determined Czechoslovak Army “which was estimated last week to require not fewer than 30 German divisions for its destruction.” And perhaps the anti-Hitler resistance, Prussian aristocrats in the German High Command, would have moved to forestall a second global conflict.

In his Commons speech, Churchill rebuked the idea of a comfortable detente with Hitler: “…there can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power, that power which spurns Christian ethics, which cheers its onward course by a barbarous paganism, which vaunts the spirit of aggression and conquest, which derives strength and perverted pleasure from persecution, and uses, as we have seen, with pitiless brutality the threat of murderous force.”

Churchill understood that totalitarianism (whether in the form of Hitler’s National Socialism or Lenin and Stalin’s State Socialism) represented an existential threat to liberal democracy, one that couldn’t be ignored or bargained away. Tragically, Neville Chamberlain never fully comprehended the nature of Nazism (how it was much more than gangsterism, and how its toxic ideology transcended the traditional nation-state), and millions paid the price for his failure.

Traitor by Jonathan de Shalit

Many observers believe that Israel’s intelligence agencies—the Mossad and Shin Bet—are among the best in the world. During the Cold War, however, the KBG and GRU (Soviet military intelligence) managed to place numerous moles in key positions in the Israeli government. Among the more prominent penetration agents were Lt.-Col. Israel Bar, a military analyst; Marcus Klingberg, an expert on chemical and biological weapons; and Col. Shimon Levinson, a senior Israeli intelligence officer. Many of these agents betrayed their country on ideological grounds, with Communist sympathies trumping Zionist patriotism.

Jonathan de Shalit’s Traitor, a bestseller in Israel translated from the Hebrew by Steve Cohen, focuses on the hunt for a long-entrenched mole, code-named Cobra, in the Israeli government, an agent recruited during the Cold War. (De Shalit is the pseudonym of a former Israeli intelligence officer). Aharon Levin, former head of the Mossad, is called out of retirement and tasked with finding Cobra. Fans of Daniel Silva’s modern spy thrillers will find the recruitment and composition of Aharon’s secret team quite familiar—including two brilliant and tough female operatives. The hunt leads to Europe, Russia, and the United States, and takes on an increasingly political cast. It’s one thing to figure out who the traitor is, it’s another to publicly expose a foreign spy in the corridors of power and risk the political damage both at home and abroad.

De Shalit is at his best in exploring the reasons for Cobra’s treason, that mix of narcissism and feelings of alienation and marginalization that often motivate penetration agents. There’s an intriguing twist—Cobra believes he has been spying for the CIA, but he has been tricked into passing information to the East Germans and the Russians. The team hunting him doesn’t care about his motives: they are eager to catch him and see him face the harshest consequences. The Israelis have always taken a hard line on the question: Soviet spy Marcus Klingberg, arrested in 1982 and tried in secret, was sentenced to 20 years in prison (and served the first 10 in solitary confinement).

Traitor offers an insider’s perspective on the challenges facing Israel’s intelligence community. There’s plenty of suspense in the frantic hunt for Cobra, and an ending that reflects the hall of mirrors that often confronts those responsible for countering espionage.

Here are past lists of top spy thrillers. You can click for:

Ten classic British spy novels

Copyright © 2018 Jefferson Flanders

All rights reserved